The Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA) is located on three hectares of land above the small coastal town of Komiža, on the island of Vis in the Adriatic Sea .

By Denise Sumi

The following text was originally written for INC Reader #18: Tactical Media Reader – Common Tools for Common Struggles, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Tommaso Campagna, Sepp Eckenhaussen, and Geert Lovink, which will be published in book form in early 2026. Many thanks to Kate Babin for proofreading.

In an era shaped by the destructive forces of (neo-)colonialism, capitalist extraction, unsettlement and climate crisis, ISSA cultivates experimentation for reconstructing and sustaining life forms and social bonds outside the logics of neoliberal governance and extinction. The school is located within the Mediterranean Sea, a position that Tiziana Terranova identifies as subaltern and a ‘laboratory for the development and testing of new technologies for the government of mobility, the securing of borders, and the military policing.’[1] ISSA is a place and mindset that experiments with traditional and new technologies, that explores ‘autonomy as a political strategy and as a model for organizing social life’, [2] countering the prevailing logics and institutions that Terranova speaks of. Focusing on self-sustained and life-integrated learning instead of discipline and disruption, here, a growing group of artists, philosophers, media scholars, journalists, and activists are building new kinds of social, material, and media infrastructures that unfold differently than the logics of late capitalism.

In autumn 2024, I attended the first major public event organized by them. I took a ferry from Split across the Adriatic Sea, next to me, an elderly man with sun-tanned and wrinkled skin was reading a biography of Tito. After embarking, I found myself on a public bus with many others, travelling along hilly roads to the other side of the island, arriving on, one would say, an idyllic vacation destination. I then walked 15 minutes along narrow, cobbled streets to a former Yugoslav socialist hotel on the seafront that, with stunning attention to design details, resembled an era unfamiliar to me. The next day, a bus picked up a group of people—art students, artists, academics, retirees, families, and activists—and drove us uphill to the actual school site. On my first day of the working action, I carried wooden planks along an earthy path for about 800 meters with strangers for several trips. We worked to prepare the future terracing, which soon would host guests, gatherings and talks under the open sky. I not only encountered some of the 200–250 people who were part of To Live Together, but also several dark grey-green salamanders that quickly hid under warm rocks when they sensed my presence. I remember the buzzing of insects and the fly-by of butterflies, as well as the distinctive scent of wild rosemary and salvia in the Dalmatian coastal area. We worked for about six hours—some building stone walls, others hunting for a 4G or 5G signal with DIY antennas, while still others cooked, rested, chatted, or provided (child) care. At lunch we were served a Naan-Aligned dish, and gradually, some of the strangers began to become familiar faces. After lunch, media hacktivist Marcel Mars introduced ISSA’s online pirate library and strategies for media resistance. More on that later.

What draws me to ISSA and what I aim to map out with my contribution, is not merely what they do, but how they do it. This is not an institution that produces knowledge as commodity, but one that understands knowledge as ecology: messy, interconnected, resistant and disobedient to extraction. This is not an institution that produces another event to be attended, but the making-present of threads, the conspiracies between ideas and bodies. Their approach is refreshingly material. Where others theorize about networks, ISSA enacts them by building together—and not as part of another Biennale or University program. Their experiments are not lab-like, temporary curiosities but affective infrastructures—ways of being together in common that generate new possibilities for learning, creating, existing. [3] They understand that pedagogy is not neutral transmission but active world-making and that teaching mustn’t be disciplinary, but can be a form of love and leisure. [4] Their tactical and strategic tools proliferate not as finished products but as protocols—ways of doing that can be adapted, hacked, reimagined by others. What strikes me most is how they hold together the theoretical and the practical without flattening either. ISSA follows the idea that there’s no divide between theorists and practitioner but ‘that the production of theory is also practice.’ [5] The site itself carries memory—layers of history that they neither dismiss nor romanticize but work with. ISSA suggests that learning might be less about acquiring and more about attuning. In a time when education increasingly resembles extraction, they insist on slow restoring and cultivation. All this feels urgent.

To Organize! Mediated Resistance

The land in the hills of Komiža belongs to private owners who have made it available to the association for a symbolic rental price for 99 years. For the core group, transparency is crucial for direct democracy and living well together. However, transparency in complex social structures that scale up might be obscured, which is why organizing, trust, and care must become equally important. Since its founding, over twenty-five ‘conspirators’ have supported ISSA’s vision with funds, advocacy, or labor. The current core group of organizers includes Marina Andrijašević, Srećko Horvat, Predrag Kolaković, Marko Pogačar, Saša Savanović, Gordan Savičić, Selena Savić, Domagoj Smoljo, and Carmen Weisskopf from !Mediengruppe Bitnik. [6] Many have biographical links to Croatia and former Yugoslavia, bringing lived experiences of different forms of collective organization. I first heard about ISSA and its public program at Berlin’s Panke.Gallery event esc return ↩: scripts for degrowth, buen vivir and living otherwise,[7] and when I registered for the public program, I was invited to join a Signal group that now connects almost 200 people.[8] It is, even now, a very active group, sharing news of student protests in Belgrade, resources on DiEM25, information on projects with similar concerns, solarpunk book tips, recipes, and more. While ISSA’s basis rests on the organization of its core group members and the material infrastructure, it extends into a communal-collective enunciation, a shared presence, intent, and its manifestation. Rather than discarding the notion of community as outdated, I argue for its continued relevance where it intersects with broader collective struggles. Within ISSA, multiple communities intersect. There is the Berlin-based community; a network connected through Croatia, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean Sea; an extended international community; the local community of Komiža; and the more-than-human communities of land and sea. As with any diverse grouping, identities diverge, livelihoods and political emphases differ. Yet the challenge remains: how to live, build, and organize together in difference, not by erasing these, but by learning to dwell within multiple worlds.

To Live Together: Social Autonomy

In asking how ‘to live together’ [9] and discussing which forms of society make a good life possible, ISSA is firmly rooted in a rich philosophical, political, and activist tradition that is left-leaning in thinking and action, critical of authority, state structures, and centralized power. The Island School stands in close vicinity to common struggles, from the communist Yugoslav partisans who fought a fascist regime on the island in the 1940s (Fig. 2), the (proto-)anarchists, the Italian autonomous movement of the late 60s and early 70s, the anti-globalization movement of the 90s and early millennium, and Critical Net Cultures or Tactical Media. Like these previous movements, ISSA positions itself critically towards liberal democracy. Instead of liberal democracy, it advocates for direct and participatory democracy, openness, heterogeneity, hospitality, mutual aid, and social instead of individual autonomy. Social autonomy builds on the basic understanding that the social fabric is always interconnected and interdependent, never based on separation or self-sufficiency for some.

The ISSA website is full of stories, writings, and conversations that inspire the project: a text by anthropologist David Graeber on Libertalia, a possible 17th-century community on the island of Madagascar founded by French pirates; a tribute to internet activist Aaron Swartz, an early advocate of digital piracy and the digital commons; a text by Henry David Thoreau, who moved to a cabin near Walden Pond in North America in the mid-19th century to live deliberately; and a text on the concept of mutual aid by the anarchist Peter Kropotkin, who argued in 1902 that for many animals cooperation was as important as competition. What is interesting here is that for thinkers like Kropotkin and Thoreau, the question of autonomy and life is not only directed at the human community. It explicitly includes non-human agents as part of the social. In contrast to most of the above-mentioned movements, this principle of interconnectedness amongst all species is reflected in the Island School of Social Autonomy’s approach for example in the way they build but also in their close exchange with artists and friends such as James Bridle or Višnja Kisić and Goran Tomka from Forest University.

While the collection of references helps to understand ISSA’s guiding principles, the voices of women* who serve as inspiration could be expanded. As part of the public program To Live Together, Silvia Federici gave an online lecture. She reminded us that no male-dominated movement, from the anarchists to the communists, has ever adequately addressed questions of reproduction and the conflict between capital and life. Whatever action we take, says Federici, must contain within it the seed of a different kind of society, one that extends towards feminists, translocal, ecological, and infrastructural concerns. ‘In today’s new forms of capitalist development, the digital economy, you cannot have an economy without practically destroying, consuming the earth, without an immense amount of extractivist activity to produce the lithium, the coltan, and the many other minerals that are necessary.’ Thus, Federici calls for a deactivation of mechanisms as a tactic, for collectivizing reproduction in a way that is not built on the exploitation of people and nature. For ISSA, this is not a nostalgic return to an imagined premodern common or localism, or the complete rejection of all digital technology, but a way of rethinking the socio-technical and social reproduction itself. Tools and infrastructures of everyday life—information technologies, food, health, learning, care—become the site where social autonomy is practiced and defended.

To Learn and Build Together: Convivial Tools

ISSA’s understanding of the tools and infrastructures that form society follows to a great extent Ivan Illich’s concept of conviviality. Illich was a critic of industrial and technocratic society with its dogma of acceleration and productivity and its tools that serve overgrowth, monopoly, over-programming, and polarization. He argued that tools are not limited to machines and hardware, but include systems that produce information, education, health, knowledge, and collective decision-making. He intended it to refer to autonomous and creative interaction between people and between people and their environment. The German dictionary translates ‘conviviality’ as ‘unbeschwerte Heiterkeit’ and ‘Geselligkeit’, meaning ‘carefree cheerfulness’ and ‘joviality’. However, in a world of genocide, terracide, and overwhelming grief, I don’t believe in ‘carefree cheerfulness’ and ‘joviality’ as endurable forces. I prefer to translate conviviality as ‘with the living’ or ‘living with’, as a communal force between all living species and matter. An active and discursive act of living with. A convivial society is one without technocrats. A convivial society is one without power holders. A convivial society might include traditional forms of governance. Each convivial society has its unique arrangements. According to Illich, the focus must be on tools that enable ‘self-initiated learning’, that are ‘least controlled by others’, that are participatory and accessible, and that cultivate an autonomy that respects planetary boundaries. ISSA is, so to speak, a real-time experiment with convivial tooling. Its planned infrastructure projects include the construction of geodesic domes, Thoreau’s Cabin, an amphitheater, electric cars and boats, an uphill zip line, a pirate radio station, a Mediterranean forest garden, a seed bank, and a local server, embodying this commitment. In the last two years, several basic infrastructure projects have been realized: the reconstruction of the 100-year-old stone house and the construction of several terraced stone walls under the guidance of local expert Igoš Matić. Wherever possible, traditional building methods and local materials such as stone and earth were used (Fig. 4.) The dry stone walling method is non-invasive and has been used in Dalmatia for centuries. Electricity has been provided by solar panels.

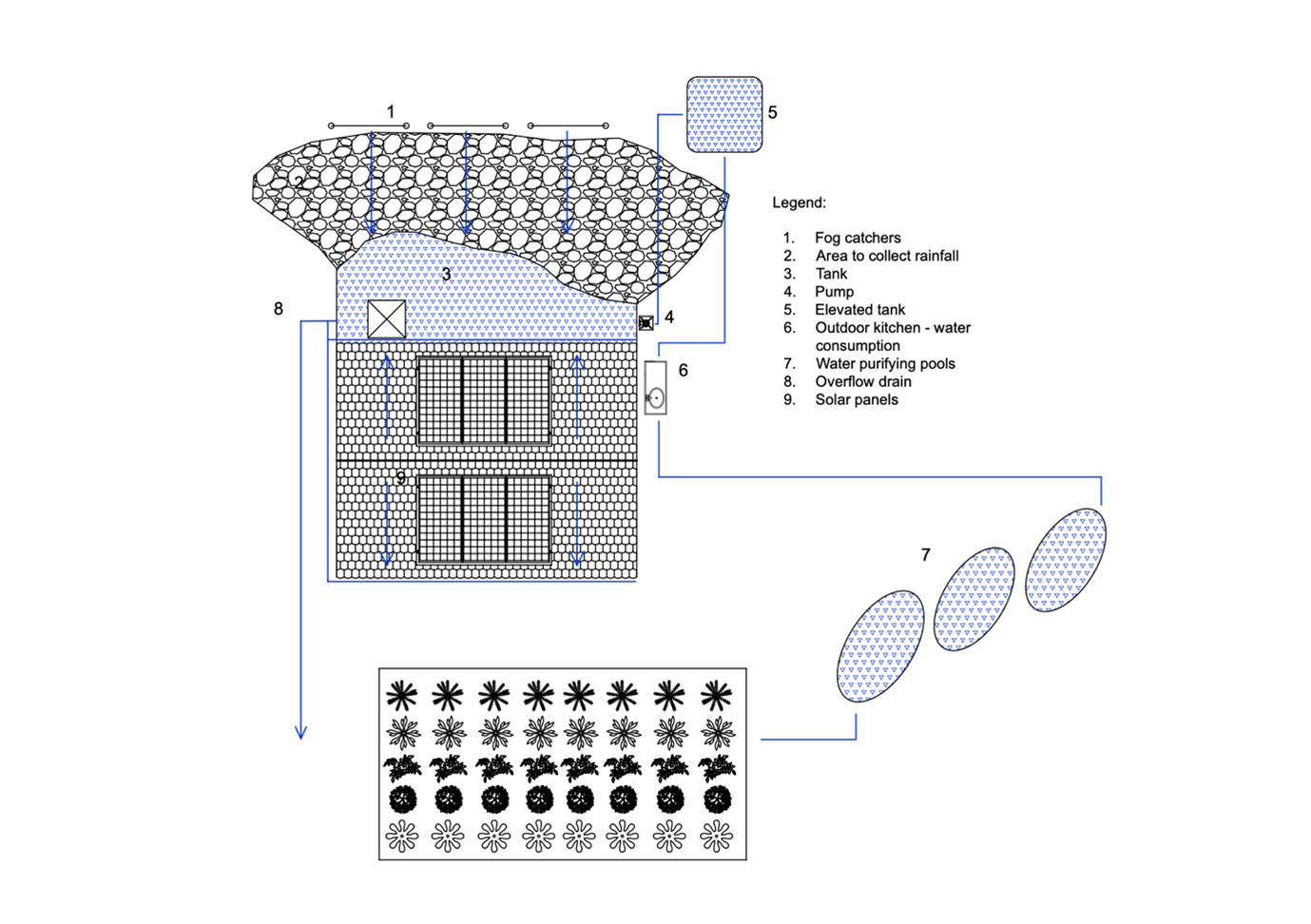

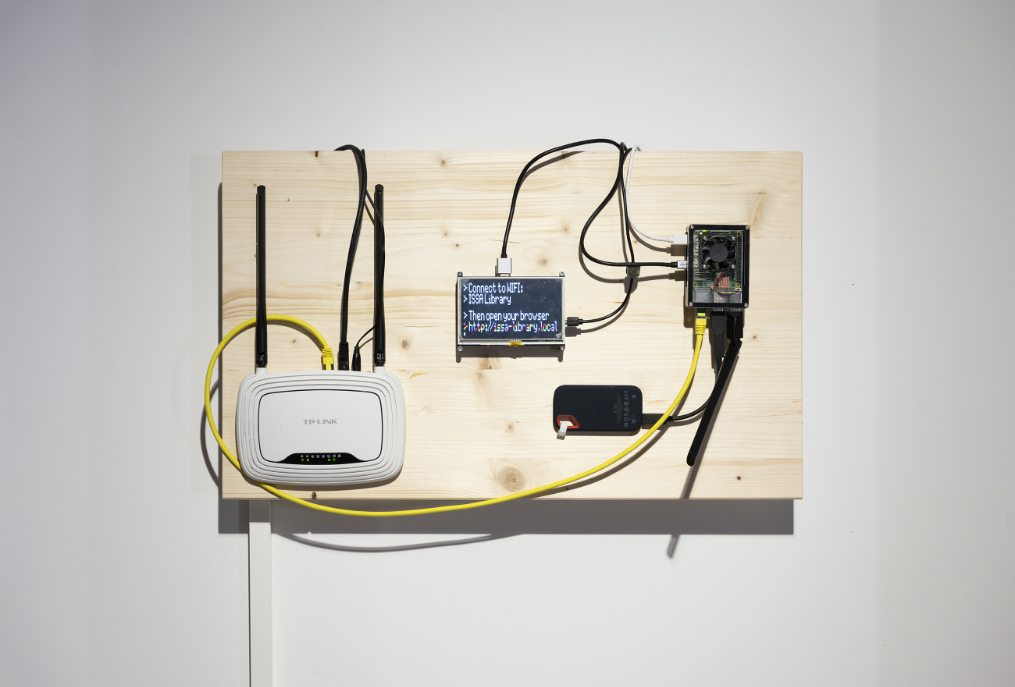

Currently under construction are a large terrace, an outdoor kitchen, compost toilets, antennas, a local server, and a forest garden, all collectively planned and built. ZMAG (Zelena mreža aktivističkih grupa, Green net activist group) was commissioned to build a circular water system consisting of a traditional cisterna, cloud collectors, water tanks, and bio-filtration systems (Fig.5 & 6). ISSA’s website is self-hosted by !Mediengruppe Bitnik, enabling local autonomy over information and digital sovereignty outside corporate cloud systems. The local server to be built on-site and powered by solar energy might become a node within the Solar Protocol, a larger network of solar-powered servers where each server only transmits data based on an environmental logic, dependent on season, the time of day, and weather conditions. The stone house serves as both repositories, housing ISSA’s physical and digital libraries. Both collections feature texts about the Mediterranean region, about radical theory, or practical ‘how-to’ pamphlets, while the digital library, based on a local file server, mirrors shadow libraries like UbuWeb with its 4TB, and sometimes another mirror travels to exhibitions and other sites (Fig. 7). Here, knowledge and infrastructure are conceptualized as commons—resources held collectively rather than privately owned. This sharing of knowledge through libraries, workshops, lectures, and community work actions creates a living pedagogy of collaborative learning, embracing the DIWO (do-it-with-others) ethos and skill-sharing that foreground collective reconstruction strategies. The title of the working actions in October 2024 was We Are Building the School, the School Is Building Us—a phrase that captures the materialist Marxist understanding that as we actively transform the material conditions around us, it simultaneously transforms our social fabric. During my stay on the island of Vis, I attended the workshop Your Own Private Pirate Radio Station (Fig. 8 & 9). Later, in 2025, in a continuous workshop as part of Wiener Festwochen, I managed to finish my first self-soldered radio transistor. It works! It may sound trivial, but this generative act of skill-sharing, of not only seeding an idea but giving me the tools to access/read books aloud or share records from my music collection with my immediate neighbors through transmission technologies—whether in the event of a breakdown or simply as a joyful tactic—changes something in my understanding of the political body towards a more caring and social habitat.

Regenerative Autonomous Zones

Many people involved within ISSA bring decades of critical engagement with information politics, media systems, computational processes, and governance in our networked world. Rather than retreating from technology, they recognize that today’s crises demand action beyond digital spaces and individualistic network culture. This isn’t prepping or anti-tech escapism, but a deliberate reimagining of how knowledge, social autonomy, and critical media infrastructure can be cultivated outside capitalist paradigms before being reintroduced to wider networks. The 1990s Tactical Media movement and Hakim Bey’s ‘Temporary Autonomous Zones’ promised political subversion through DIY, hedonistic, community-based approaches, and spontaneous moments of insurgency against information hegemony. [16] Where Tactical Media prioritized guerrilla interventions into existing systems and media subversion through websites, videos, and hacking, ISSA focuses more on building material autonomy through learning and infrastructure development. ISSA seems to shift from temporary insurrections to lasting infrastructures, from representational politics to embodied, relational practices that are regenerative, sustainable, and place-based without being place-bound. Unlike earlier movements concerned with collective deliberation across the whole social factory, or their hope in the global potential of the multitude, [17] ISSA focuses on the community, the place-based, the small-scale and the materializing, while remaining open and regenerative. Their hope lies not in singular solutions but in archipelagos of autonomous zones that persist rather than dissolve, engage rather than disrupt, and relate with place and material rather than isolate. ‘From the “free software” to the “solidarity economy” movement’, Federici and George Caffentzis point out that ‘“time banks”, urban gardens, seed banks, Community Supported Agriculture, food coops, local currencies, “creative commons”, shadow libraries, open syllabi, bartering practices – all represent a crucial means of survival. ’[18] With this in mind, it becomes obvious that ISSA is not meant to be replicated one-to-one elsewhere—different sites and communities need different tools and topics—but that its pedagogical approach might be a model to share.

The integrating of self-initiated learning, skill-sharing, and thinking and doing, the application of open protocols rather than solutions, and the focus on the social rather than the individual—these modes can serve as a model for radical local autonomies or testing grounds for direct democracy in other contexts. From the land uphill, from the local community of Komiža to the Paris Commune, to the Pro-Palestinian protests, to the student protests in Serbia, ISSA finds alliances and learns from and with them. To freely paraphrase Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, a founding friend of the project, we cannot control the whole force of global (media) dynamics, but we can steer smaller processes and continue to create many worlds of sociability. I wish for the future not to belong to fortresses at the center nor to gated bunkers, but to many networked islands at the margins—slowly and reflectively constructing convivial tools for worlds yet to come.

Denise Sumi is a PhD candidate at Weibel Research Institute for Digital Cultures at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. In her research she focuses on artistic practices that embrace technology-based relationality, transversal knowledge exchange, and collective approaches that establish and sustain a socially and ecologically responsible life with technology in a networked world.

References

[1] Tiziana Terranova and Iain Chambers, “Technology, Postcoloniality, and the Mediterranean,” e-flux Journal, no. 123 (December 2021): 12-21, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/123/436918/technology-postcoloniality-and-the-mediterranean/.

[2] Island School of Social Autonomy, “About”, https://issa-school.org/about.

[3] In her 2019 editorial for the transmediale journal, Daphne Dragona introduces the term ‘affective infrastructures’, defining them as ‘alternative architectures of association and resistance’ with reference to scholar Lauren Berlant. Daphne Dragona, “Affective Infrastructures Editorial,” transmediale, October 31, 2019, https://transmediale.de/en/journal/affective-infrastructures-0.

[4] In Deschooling Society, Ivan Illich refers to Thomas Aquinas who understood teaching as an act of love. He also draws upon the Greek term ‘schole’ that meant leisure. Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society (1970, reprint Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023), 101.

[5] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, eds. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 275.

[6] This is by no means an exhaustive list, and these names have been joined by others with varying activities and degrees of intensity.

[7] The symposium took place on June 1–2, 2024, and was part of the project find.select.transform – Resiliente Netzwerke in einer verletzten Welt at Panke.Gallery, Berlin, https://www.panke.gallery/event/esc-return-scripts-for-degrowth-buen-vivir-and-living-otherwise/.

[8] Lately, all members of the Signal group have been invited to an online meeting to get more information about how to get involved. At this point, five working groups exist, covering the topics: Funding; Care & Organization; Infrastructure & Land; Digital Infrastructure; and Learning & Education.

[9] To live together was the title of the first public program, taking place from October 4 – 9, 2024. Island School of Social Autonomy, “To live together,” https://issa-school.org/to-live-together/.

[10] Henry David Thoreau, Walden; or, Life in the Woods (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854).

[11] Island School of Social Autonomy, “Inspiration,” https://issa-school.org/inspiration/

[12] Island School of Social Autonomy, “Conversation with Silvia Federici,” https://issa-school.org/reflections/conversation-with-silvia-federici/.

[13] Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (New York: Harper & Row, 1973), 11.

[14] STARTS4waterII residency in collaboration with Drugo More, https://drugo-more.hr/en/starts4waterii-challenge6-issa/.

[15] Solar Protocol by Tega Brain, Benedetta Piantella, and Alex Nathan, https://www.solarprotocol.net/.

[16] Hakim Bey, T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism (New York: Autonomedia, 1991).

[17] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 22–41.

[18] George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici, “Commons Against and Beyond Capitalism,” Upping the Anti, 2020, 95.

Image Credits

Fig. 1 The Island School of Social Autonomy is located on three hectares of land above the small coastal town of Komiža, on the island of Vis in the Adriatic Sea, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 2 “A Tour Through Revolutionary Island” with Srećko Horvat , CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 3 Learning with Pirate Care, “For a Global Mutiny Against an Empire of Negligence, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 4 Collective working action “We Are Building the School, the School Is Building Us” and “Dry Stone Walling” with Igor Mataić, udruga Pomalo, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 5 Getting insight from Matko Šišak into the infrastructure project “Circular Water System as Convivial Tools” by ZMAG, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 6 Construction diagram for the project “Circular Water System as Convivial Tools” by ZMAG, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 7 ISSA – Island School for Social Autonomy, ISSA Library, 2024, Tools for Change, 2024, HEK, photo: Franz Wamhof

Fig. 8 Participants of the workshop “Your Own Private Pirate Radio Station” by !Mediengruppe Bitnik, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.

Fig. 9 Building “Your Own Private Pirate Radio Station” with !Mediengruppe Bitnik, CC 4.0 by ISSA School / BONK productions.