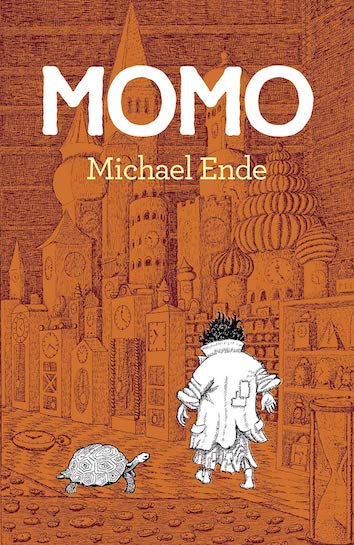

(or the strange story of the time-thieves and the child who brought the stolen time back to the people)

Calendars and clocks exist to measure time, but that signifies little because we all know that an hour can seem as eternity or pass in a flash, according to how we spend it.

― Michael Ende, Momo

Michael Ende, the German fantasy and fiction writer best known for his novel Neverending Story wrote a less well-known but equally beautiful children’s book called Momo a few years earlier, in 1973. Chances are you came across and read it as a kid, and if not, we would recommend it wholeheartedly.

This story is about a special little girl with a remarkable skill: she listens, really listens, and by doing that, she is able to help people. Everyone in her neighbourhood recognizes her and rushes to her, an illiterate and parentless girl in a shabby coat. Her world changes when the strange Men in Grey arrive, convincing everyone to start saving time in their Timesavings Bank. Soon the world turns as grey as they are, and it is left to Momo to save it.

This reminds us all of something—that’s right, the Dalmatian philosophy of pómalo. As one of the book’s characters, a sweeper named Beppo, says:

“It’s like this. Sometimes, when you’ve a very long street ahead of you, you think how terribly long it is and feel sure you’ll never get it swept.

He gazed silently into space before continuing. ‘And then you start to hurry,’ he went on. ‘You work faster and faster, and every time you look up there seems to be just as much left to sweep as before, and you try even harder, and you panic, and in the end you’re out of breath and have to stop – and still the street stretches away in front of you. That’s not the way to do it.’

He pondered a while. Then he said, ‘You must never think of the whole street at once, understand? You must only concentrate on the next step, the next breath, the next stroke of the broom, and the next, and the next. Nothing else.’

Again he paused for thought before adding, ‘That way you enjoy your work, which is important, because then you make a good job of it. And that’s how it ought to be.’

There was another long silence. At last he went on, ‘And all at once, before you know it, you find you’ve swept the whole street clean, bit by bit. What’s more, you aren’t out of breath.’ He nodded to himself. ‘That’s important, too,’ he concluded.”