Towards Archipelagos of Permanent Autonomous Zones

It all started with a sort of conspiracy.

Now you probably think we’re crazy – flat-earthers, lizard people believers, X-Files fans, Davos conspiracy theorists, chemtrail enthusiasts, deep-state believers, Pizzagate supporters… or maybe a whole universe of conspiracies comes to mind.

Conspiracy obviously became a bad word.

Everything became a conspiracy, and conspiracy became everything.

These days, just like genocide, conspiracy is live-streamed.

Who would be crazy enough to proclaim to be a conspirator.

But what if there is no collective action or understanding of the world without conspiracy?

When we say it all started with conspiracy, we think of the original, primordial conspiracy: the conspiracy of breathing together, not simply living together, in the same rhythm or in many different ones.

Among perceptive thinkers, at least three of them have deepened our understanding of conspiracy in relation to breathing and rhythm. One is the great educator Ivan Illich, the other is the semiotician Roland Barthes, and last but not least, our own conspirator Franco “Bifo” Berardi.

In his lecture “The Cultivation of Conspiracy”, given in 1998 on the occasion of receiving the Culture and Peace Prize of Bremen, Illich reminds us that the origin of the word conspiracy and the prototype of conspiracy lies in the celebration of the early Christian liturgy in which, no matter the origin, men and women, Greeks and Jews, slaves and citizens, engender a physical reality that transcends them. The shared breath, the con-spiratio, is the peace understood as the community that arises from it.

“Community”, says Illich a few years before his death, “is not the outcome of an act of authorative foundation, nor a gift from nature or its gods, nor the result of management, planning and design, but the consequence of a conspiracy, a deliberate, mutual, somatic and gratutious gift to each other.”

The original meaning of conspiratio, which brings us closer to Roland Barthes, comes from the mouth-to-mouth kiss among the faithful attending services: originally it represented a commoning of breath.

At his late lectures at Collège de France, later published as How To Live Together, Roland Barthes became captivated by communities in which everyone follows their own rhythms, while at the same time there are parts of the community that have a common rhytm. The main objective of these communities, according to Barthes, was “to safeguard rhuthmos, that is to say, a flexible, free mobile rhythm; a transitory, fleeting form, but a form nonetheless”.

These kind of “idiorryhythmic constellations” and forms of living together came to life in the Syrian and Egyptian deserts. Throughout human history anchorites, hermits, and outcasts sought to escape the rules and control of higher powers. The rhythm Barthes researched was a rhythm “that allows for approximation, for imperfection, for a supplement, a lack, an idios: what doesn’t fit the structure”.

“There is a consubstantial relationship between power and rhythm”, warns Barthes, “before anything else, the first thing that the power imposes is a rhythm (to everything: a rhythm of life, of time, of thought, of speech.”

In his book Breathing: Chaos and Poetry, published just a year before the brutal murder of George Floyd and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the conspirators behind ISSA, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, claims that the words “I can’t breathe” expresses the general sentiment of our times:

“Physical and psychological breathlessness everywhere, in the megacities choked by pollution, in the precarious social condition of the majority of exploited workers, in the pervading fear of violence, war, and aggression.”

It is precisely respiration that, according to Bifo, can help us understand the contemporary chaos: the process of “breathing with chaos” or “chaosmosis”, which he defines as ‘osmosis with chaos’, is where a “new harmony emerges, a new sympathy, a new syntony.’”

We need to not only learn how to breathe together again but also how to breathe with chaos.

“Dream Valley” on Vis

When we first arrived to the “Dream Valley” on the island of Vis, a dense, overgrown pine forest covered the land.

The last time it was cultivated was more than half a century ago, half a century before we placed our feet and hands on it – to establish a school from the future, on a remote Adriatic Island.

The only remnants on that hill near Tito’s cave, for several centuries cultivated as fruitful vineyards, were the ruins of an old stone house once used for wine storage and a small area to shelter a donkey, the true proleterian among animals.

The donkey, one of the symbols of the Meditteranean, was domesticated approximately five to seven thousand years ago in Africa and since then, after spreading rapidly through Eurasia, it was mainly used for work. Donkeys were champions of carrying. But we could find none on our island to help us carry the material uphill in order to reconstruct the old stone house.

The glorious – and strenuous – time of the donkey, at least in this part of the world, was done. The owners of the few remaining donkeys on the island rightly concluded that borrowing them for our crazy project would be too demanding on the first proletarians.

So, we had no other option but to carry quite literaly tons and tons of material: from wood, sand and gravel to tools and hundreds of books by hand and foot. Luckily, thanks to an early donation by our only seemingly unlikely conspirator, Pamela Anderson, the first tools we invested in – after realizing the symbol and soul of the Meditteranean is disappearing – were “electric donkeys”.

We still carry tons of material uphill by hand and foot, but now we at least have the benefit of modern technology: two electric wheelbarrows. But even with our “electric donkeys”, our project still sometimes reminds us of a Mediterranean version of Fitzcarraldo.

We are not Klaus Kinski in Werner Herzog’s movie transporting a steamship over the Anders mountains to build an opera house, but we are determined to build our School in the forest in the hills, with no option but to carry everything uphill.

We do not plan to build an opera house, that is a bit too bourgeois for us. Although even an opera could take place here.

Besides renovating the old stone house and transforming it into the headquaters for the island school – with water and solar power, compost toilets and showers, classrooms in the middle of nature, residencies, and a library – we are also dreaming of creating an amphitheater in the “Dream Valley”.

The part of the island where ISSA is being born is originally called Sinova dolca (the “Son’s Valley”), but also S’nova dolca, which could be interpreted as “Dream Valley”. At least that is the meaning we like to ascribe to it.

Who are we and why are we doing this?

At first, people thought we were crazy. Many islanders probably still think so.

Why would anyone, in times of global tourism and global crisis, invest their time and life into something so slow and without any financial profit?

Why would anyone build a school on a remote island in the midst of the Adriatic Sea, in a part of the island that was abandoned overgrown by forests for more than half a century?

Who are we?

We are wild dreamers, artists and poets, philosophers and activists, drystonewallers and builders, who got tired of waiting for the “day after”, the day after a fundamental event that would change the contemporary way we live together, not only among humans, but among other species, with animals and all other sorts of living beings, including our only planet.

Why are we doing this?

We are not preppers. We are not preparing for the “day after” the cataclysm. We know it has already happened.

We are not merely concerned with our own survival nor are we interested in surviving for survival’s sake.

Unlike the current-day preppers, with their private jets, nuclear bunkers, libertarian cities and escape plans to New Zealand or Mars, we are not abandoning humanity or the planet.

As D. H. Lawrence memorably said in Lady Chatterley’s Lover:

“Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes… We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen”.

We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen.

But how do we need to live?

What kind of habitats can we and must we build?

Slowly, we arrive at the age-old question of philosophy: What is “good life”?

And what is “good life” in our contemporary times, in the end of times, in times of extinction?

But before, if ever, we arrive to a proper – ontological, ethical, political, social – answer to this crucial question, we must go back to the island, to this place on Earth that was always, even when it was still a mountain, connected to the mainland.

And before we come back to the future island, we must place it somewhere.

We must place it in the archipelago.

What is an archipelago?

The most common definition of an archipelago is a “group of islands”, but this standard definition mainly addresses its spatial dimension.

An archipelago is not only temporal occurrence, it is both spatial and temporal, geological and cultural, natural, and artificial.

The word archipelago originally comes from arche, from the Greek word for “original”, “principal”, “source of action”, “first principle”, and pelago, meaning “deep”, “sea” and – “abyss”.

Interestingly, the great Croatian poet Tin Ujević, in his beautiful text on the island of Vis, Komiža and the archipelago where we founded ISSA (“Nit u srcu mora: Komiža na Visu“, 1930) mentions the connection between the origin of the word of Adriatic and its relation to the abyss:

“Finally, in a mournful, bathed wasteland, I personally rehearsed an impossible thing, happiness. It was an escape from all the pressures of reality. Here I took into my soul all the infinite seas on which I have never vomited, and who would not want to live like this in nature, in an oceanic, Otahite happiness? I said: Vis is dearer to me than the entire Adriatic, and Saint Andrew is even dearer to me than Vis. Atlantic and Pacific waters come to me, not just the Adriatic. And that Hadria, I told the listeners, comes from the Dravidian word ‘Hodru’, which in Dravidian means Abyss (abyss), because in ancient times, water really broke through here and submerged inhabited and cultivated areas.”

Geological evidence we have today proves that, indeed, that is how the Adriatic was created when water submerged the land.

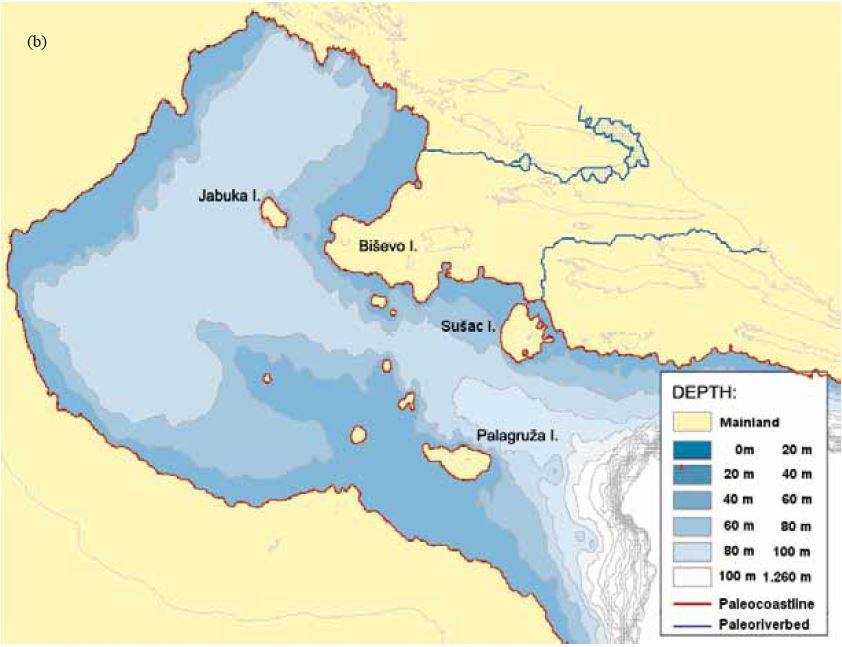

This archipelago and its future islands were a result of an abbys of gigantic proportions, a consequence of an underwater volcano more than 220 million years ago, when the supercontinent Pangea still dominated the world.

Around 20,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, sea levels began to rise in the Adriatic region. From the top of the hill at ISSA, we can see what is now called Dalmatia and the highest parts of the Dinaric Mountains along the eastern coast of the Adriatic. All the islands we can see from here – Hvar, Brač, Korčula, Pelješac – were once part of the mainland.

Before the ice started melting, the Adriatic Sea was 120 meters lower, and hunter-gatheres were still roaming through its valleys. As sea levels began rising, soon they had to adopt and find other ways of survival. Now, it was the sea that was the future. Then came the agricultural revolution, herding and domestication of animals. And the donkeys.

But it would be wrong to think of the Neolithic and agricultural revolution as an event, a sudden change, like a rapid rise in sea levels and hunter-gatherers immediately stopping hunting for animals and becoming fishermen. The available data shows that the Neolithisation of the Adriatic was a complex and arrhytmic process that took almost a thousand years to establish.

Here the recent book by David Wengrow & David Graeber, Dawn of Everything, is useful to get a better understanding of history as an archipelagic process itself.

Unlike Steven Pinker or Yuval Noah Harari and their teleological notion of history connected to the ideology of “progress”, Wengrow and Graeber convincingly argued that long after the agricultural revolution, there was no fixed model of social organisation but a multiplicity of social arrangements. In short, our prehistory was not uniform but consisted of myriad forms of living together – even before the agricultural revolution, there were large cities, some monarchies, some egalitarian, others were seasonal.

In short, history and social change itself is an archipelagic process.

So, what is an archipelago?

It is a document of a previous catastrophe, of many previous catastrophes.

And of renewal, at the same time.

What was once a catastrophe is now today’s archipelago.

What was once a mountain, is now an island.

An archipelago is evidence of both revolution and evolution.

What is an island?

An island, even though the word in many Slavic languages originates from “stream” and “current” (Croatian otok from tok, teći okolo, Serbian ostrvo from struja, stream, Slovak ostrov, Ukranian ostriv), is not simply a place sourrounded by water.

As Gilles Deleuze notes in Desert Islands: “It is an island or a mountain, or both at once: the island is a mountain under water, and the mountain, an island that is still dry. Here we see original creation caught in a re-creation, which is concentrated in a holy land in the middle of the ocean.”

In other words, to perceive an island as an island would mean not to perceive geology, the vast past and major planetary events that have led to what would become future islands.

Deleuze goes on even more poetically:

“Some islands drifted away from the continent, but the island is also that toward which one drifts; other islands originated in the ocean, but the island is also the origin, radical and absolute. Certainly, separating and creating are not mutually exclusive: one must hold one’s own when one is separated, and had better be separated to create anew; nevertheless, one of the two tendencies always predominates. In this way, the movement of the imagination of islands takes up the movement of their production, but they do not have the same objective. It is the same movement, but a different goal. It is no longer the island that is separated from the continent, it is humans who find themselves separated from the world when on an island. It is no longer the island that is created from the bowels of the earth through the liquid depths, it is humans who create the world anew from the island and on the waters. “

So, what is an island?

An island is primarily a possibility to construct not only a different spatiality, but a different temporality, ways of living-together, of co-breathing, of having a rhythm or idiorhythmy.

An island is also an object of desire.

A sort of utopian desire: from Plato’s travel to Sicily in order to convince a tyrant of his ideal society, Thomas More’s Utopia depicting a fictional island society, Shakespeare’s The Tempest taking place on a remote magical island, Aldous Huxley’s Island, the legendary pirate haven Libertalia placed on Madagascar, or even Hollywood blockbusters such as The Beach with Leonardo di Caprio placed on Thailand (and ruined its beautiful beach by over-tourism).

But an island also, very often, turns out to become a dystopia. Think of William Golding’s Lord of Flies set on a remote, uninhabited tropical island or of, more recently, Hunger Games set in a post-apocalyptic archipelago and Michel Houllebecq’s The Possibility of an Island.

When you think of islands, it is impossible not to think of colonialism and imperialism at the same time.

You can also think of Próspera, a private libertarian island in Honduras. Or you could think of Praxis.

But be warned: this is not to be confused with the famous 20th century Yugoslav philosophical school called Praxis which organized the Korčula Summer School on an Adriatic island. The new Praxis is another libertarian dream of a private island somewhere in the Mediterranean.

As long as there are islands, the tension between utopia and dystopia was and always will exist.

And we are not ashamed to be called naive, romantic, or even crazy for trying to bring to life the utopian desire of our future islands.

A gratuitous gift to each other

As we carry tons of material uphill, while we build and share our breaths and rhythms in the “Dream Valley”, we are not simply building a school. The school is, as we love to say, building us.

What we are learning once again is how to breathe together – how, through cooperation and the pure joy of community building, we can create something bigger than ourselves, both in terms of the individuals involved and temporality behind and in front of us.

We have learned patience and pomalo from the island through its nature, the climate, the winds, and the waves, its people, and its traditions.

We have also learned that we must embrace – following the footsteps of the great philosopher from Martinique, Édouard Glissant – the archipelagic thought as an alternative epistemology and way of thinking that accepts ambiguities, different rhythms, ruptures, and interactions of all sorts.

Unlike the continental thought, this archipelagic, southern thought – and practice (praxis) – challenges the universalistic idea of thought promoted by the Enlightenment, which not only diminished all non-Western knowledge, but also prepared ground for imperialism, colonialism and totalitarianism.

In his essay on Herman Melville, Gilles Deleuze writes about an affirmation of the world as process and as an archipelago. He understands archipelagoes as a “world in process,” which is connected to multiplicity.

It all starts from “the affirmation of a world in process, an archipelago. Not even a puzzle, whose pieces when fitted together, would form a whole, but rather a wall of loose, uncemented stones, where every element has a value in itself but also in relation to others: isolated and floating relations, islands and straits, immobile points, and sinuous lines. ”

And it is here where we arrive at a quite unexpected encounter. The encounter between Deleuze and one of our favorite activities at ISSA – namely, dry stone walling.

Building uncemented stones has been an integral part of the Mediterranean for centuries, even millenia. The function of dry-stone walls vary and can be all at the same time – protection against soil erosion, collection of water, protection against wind, landscape architecture…

What Deleuze, although you never imagine him as a dry stone waller, points towards are the archipelagic nature of the stone walls themselves. While walls are usually built to divide, they were also used to connect and provide well-being to communities around the Meditteranean.

We are not only interested in learning from those who have thought future islands in myriad ways before us, we are keen to learn from dry stone walls, from the oak tree in front of our School, from the cicadas and their ryhthms, from the winds and from the island itself.

We are not interested in building a sort of a temporary autonomous zone. We know everything is temporary.

Yet there is also eternity by the stars, as Louis-Auguste Blanqui, another great conspirator who spent over half of his adult life in jail, declared in his “astronomical hypothesis” in the year of the Paris Commune.

In this eternity by the stars, we are opening our sails towards archipelagos of permanent autonomous zones.

These zones already exist in many places of the world, as a consequence of conspiracy, a deliberate, mutual, somatic, and gratuitous gift to each other.

We are not the first, and hopefully not the last.

Srećko Horvat, September 2024, Vis