As crazy as it sounds, it is possible – and, indeed, likely – that the ancient Greek philosopher Plato visited Vis. Unfortunately, there are no traces of his possible stay yet: even though Issa represented the most important polis in this part of the Mediterranean, not even 10 % of the 120,000 m2 of the ancient city has been excavated until today.

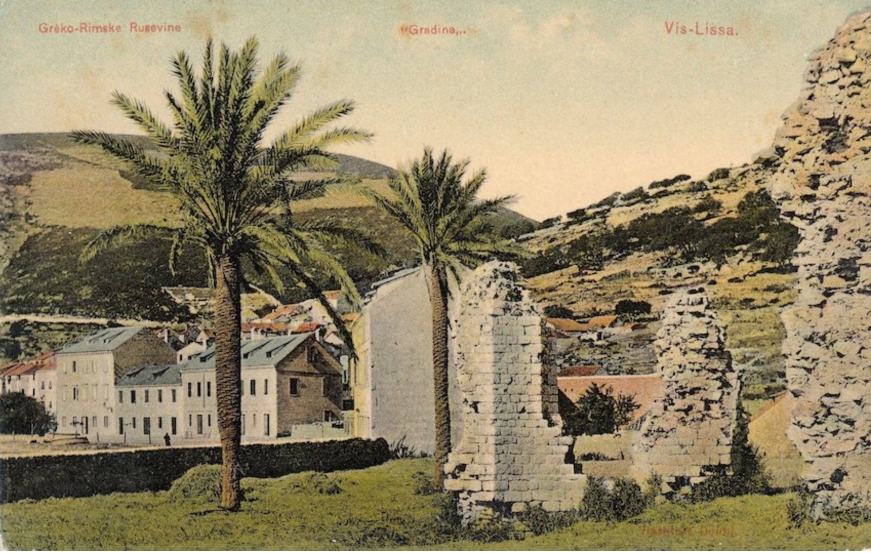

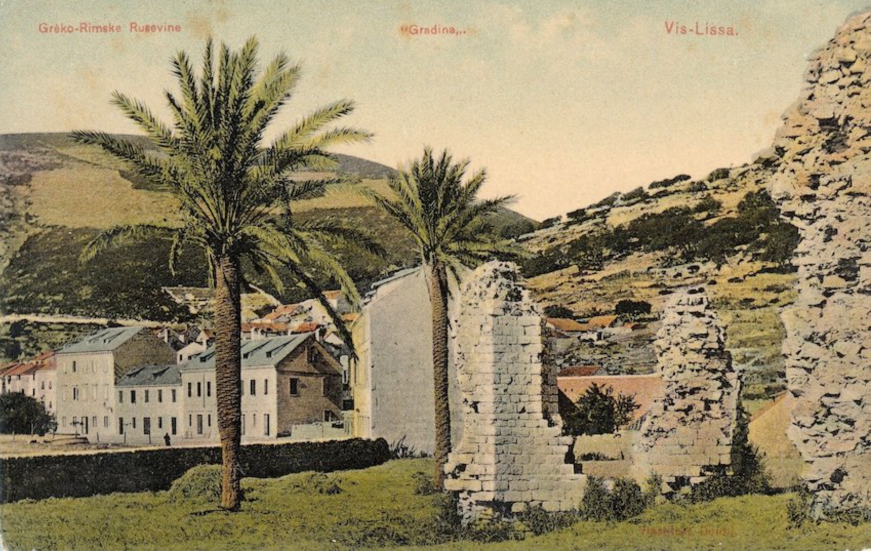

Vis has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. It was in 397 BC that the Greek tyrant of Syracuse, Dionysius the Elder, founded the colony of Issa on the island that would later become an autonomous and independent polis and establish its own colonies – the most notable of which is today’s Split. Dionysius the Elder, a tyrant of the worst kind who would later appear in Dante’s Inferno, was known for transforming Syracuse into the most powerful city in the Greek world, with an empire extending from Sicily to Italy and the Adriatic island of Issa, from which the name Vis derives.

He was also known for inviting the philosopher Plato, around 40 years old at the time, to visit his court in Sicily in 388 BC. Plato, who was dreaming of philosopher-kings and wanted to integrate politics and philosophy to create the perfect society, was of course chuffed by the invitation, and soon he befriended Dion, the tyrant’s brother-in-law, who accepted his ideas with enthusiasm. However, the tyrant didn’t like Plato’s philosophy at all. First, he wanted to kill him, and only after Dion’s intervention, Plato’s life spared and he was instead sold as a slave. He was recognized at a slave market in Aegina (Greece), where he was redeemed by Anikeris, who didn’t want to take the money that Plato’s pupils collected to free their teacher.

This ransom money was instead used to buy a plot of land in the grove of Hekadem, surrounded by olive trees, where the school of philosophy called Akademia was founded. In other words, the creation of Plato’s School in 387 BC – ten years after the foundation of Issa – could perhaps be understood as a consequence of his first failed voyage through the Mediterranean Sea to Syracuse. As we know, the most famous student would soon become Aristotle, who after studying at the Academy for almost twenty years went on to tutor Alexander the Great and later founded his own school at the Lyceum, which would later turn into the Peripatetic School of Philosophy due to Aristotle’s tendency to walk while teaching.

In 367 BC, exactly thirty years after the foundation of Issa, Dyonisous the Elder died and was succeeded by his son Dionysus II. He was young and a tyrant as well, but Dion succeeded in convincing him to invite Plato to Syracuse again. After his initial hesitation (who wouldn’t hesitate after already being almost killed and sold into slavery?), Plato accepted the invitation and visited Sicily for a second time. But again, the new tyrant didn’t like his ideas, suspecting they would undermine his own position, so Plato was detained. He was eventually set free and returned to Greece, where he would continue teaching at his Academy. Now it already sounds like Plato’s “Groundhog Day,” but in 360 BC, despite all the awful experiences he had already encountered, he accepted the third and final invitation to Syracuse. He would again end up disappointed. Around that time, the tyrant’s empire was already collapsing, and Issa wasn’t a colony of Syracuse anymore; it turned into an independent polis that started to build its own empire in this part of the Adriatic Sea and the Adriatic coast of modern-day Croatia.

Recent and older archaeological, historical, and seafaring evidence suggests that the route Plato may have travelled to Syracuse was one of the most important ancient seafaring routes used by the Greeks at that time. It followed the string of islands that stretched from the coast of present-day Split via Hvar (Pharos) and Vis (Issa). The historical and archaeological evidence from these colonies and later poleis, including the numerous caves found on both the islands of Hvar and Vis, evoke important elements of Plato’s Republic, such as land division or polis public institutions, and possibly even the famous Allegory of the Cave.

According to Harald Haamann’s recent book Plato’s Philosophy: Reaching Beyond the Limits of Reason, “Plato could have joined the various groups of founding colonists and tried to persuade them to implement his vision of an “ideal state.”In theory, Plato could have also visited Issa and maybe he contributed to the foundation of the new polis.

Whether Plato visited Issa or not, we may never find out, but Plato’s comparison of philosophy to a second navigation, the one that starts when favorable winds stop blowing and the ship remains immobile, is even more pertinent today. The role of philosophy is precisely to navigate when sailing has become impossible. The philosopher is a navigator who gazes at the stars and sky and understands the seasons and winds, including the play of shadows in the cave. What if, instead of sailing to Syracuse, Plato simply decided to stay on Issa? And what if, unlike Plato’s desire, we do not need philosopher-kings anymore but a simple and modest community of navigators?