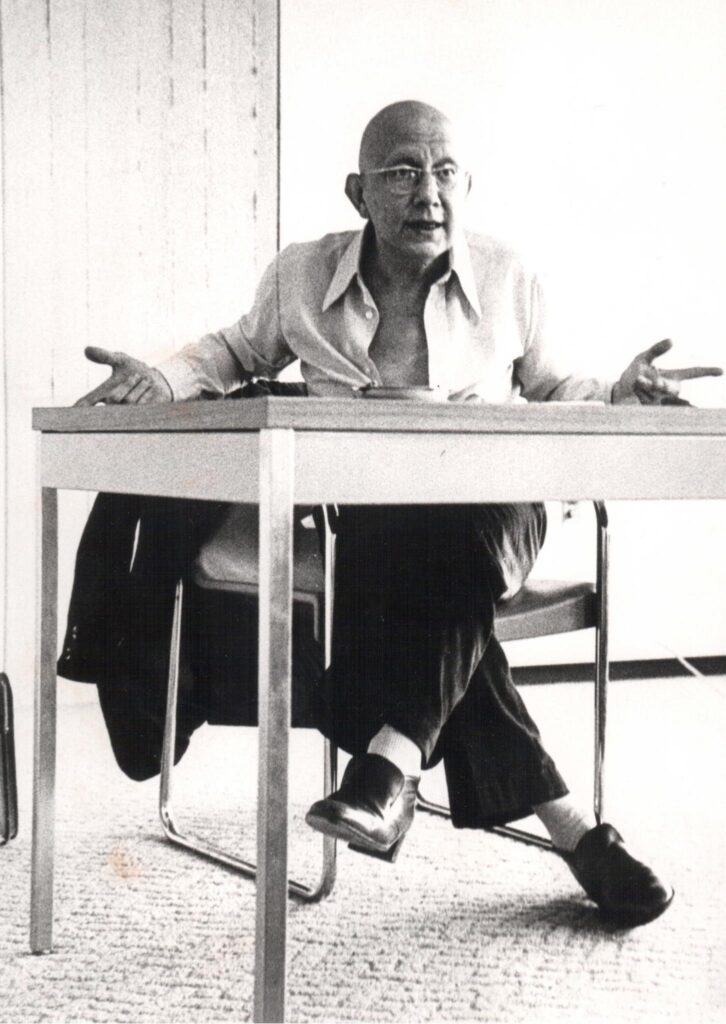

The following reflection on the ecological movement and concept of autonomy by the Greek-French philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis comes from a meeting on “The Antinuclear Struggle, Ecology and Politics” held on 27 February 1980 at Louvain-Ia-Neuve, Belgium. The other principal speaker was Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the former May 1968 Paris student leader and later German Greens Pany member. Cornelius Castoriadis has been one of the most important and innovative philosophers of the second half of the 20th century who formulated a new political theory rooted in the concept of “autonomy”. Castoriadis gave a brief but potent definition of autonomy during an interview, where he explained: “You know, in the word autonomy, two roots exist. Αυτός (me, myself) and νόμος (law). But most people think of the root αυτός and forget the root νόμος. Autonomous is he who gives to himself a law. Of course, I wouldn’t call autonomous a person that fulfills his wishes without any control …This also applies to society. Social and collective life cannot exist without an organization and without a minimum of social rules and purposes … The autonomous society is a society that knows that there is no transcendence, no transcendent source of institutions and laws, no life after death (a thing that the ancient Greeks, who did not believe in life after death, knew). The members of this society know for sure that, what is going to happen, has to be done by them, and then offered to themselves and to the society as a whole. It’s a society that knows the art of making institutions and laws for itself. This sort of ‘self employment’ guarantees the project of autonomy and defends the interests of society, since it allows its members to exist as autonomous individuals within its framework”

I am happy to be here and to see you. And I am very surprised by the number of participants, very pleasantly surprised and happy. But at the same time, this increases my fear of disappointing you, in as much as when I spoke with Dany before coming here he told me that he did not know what he was going to say, that he would improvise. Well, he has a habit of doing that and as one knows, historically, he comes out quite well. [Laughter.] As for myself, I would have liked to have devoted more time than I was able to preparing what I wish to say to you.

But perhaps, in the last analysis, this would not have made a difference since the four or five things I have to say, you will see, end in the interroga tory mode and they would have ended that way in any case. And I believe that the point of an evening like this is precisely to get you to speak, either on the questions that for you are already open or – and this would be a considerable gain – on new questions that would arise in the course of the debate, perhaps with the help of those who have been charged with introducing it.

Today, everyone knows, everyone thinks they know – this was not the case a short time ago – that science and technique are in their very essence inserted, inscribed, rooted in a given institution of society. Likewise, everyone knows that the science and the technique of today have nothing transhistorical about them, have no value that lies beyond question; these belong, on the contrary, to the social-historical institution that is capitalism as it was born in the West a few centuries ago.

That is a general truth. People know that each society creates its technique and its type of knowledge, as well as its type of transmission of knowledge.

People know, too, that capitalist society not only has gone very far toward the creation and the development of a type of technology that distinguishes it from all others but – and this also distinguishes it from all others that it has placed these activities at the centre of its social life and granted them an importance they did not have previously or elsewhere.

Likewise, everyone knows today, or everyone thinks they know, that the alleged neutrality, the alleged instrumentality of technique and even of scientific knowledge are illusions. In truth, even this expression is in adequate, and it masks the essential aspect of the question. The presentation of science and of technique as neutral means or as instruments pure and simple is not a mere ‘illusion’: it is an integral part ofthe contemporary in stitution of society – that is, it partakes of the dominant social imaginary of our age.

This dominant social imaginary can be encapsulated in one sentence: The central aim of social life is the unlimited expansion of rational mastery. Of course, when one looks from close up – and it is not necessary to go very, very close to see it this mastery is a pseudomastery, this rationality a pseudorationality. That does not stop it from being the core of the social imaginary significations now holding society together. And this is not only the case in the countries of so-called private or Western capitalism. It is equally the case in the allegedly socialist countries, in the countries of the East, where the same instruments, the same factories, the same organiza tional procedures and knowledge procedures are equally put in the service of this same social imaginary signification, namely, the unlimited expansion of an allegedly rational alleged mastery.

Here I shall open a parenthesis, for in no way can we discuss these matters in abstraction from the serious things now going on around the world. We see much more clearly today, with Afghanistan – more exactly, I shall say: People can see; as for myself, I claim to have seen it for going on thirty-five years – that the coexistence and the antagonism of these two subsystems, each of which claims to have a monopoly on the way in which ‘rational mastery’ over everything shall be attained, are now reaching the point where we run the risk of total rational mastery by the one true master, as Hegel would say, that is, by death.

You know that the domination of this imaginary begins first via the form of the unlimited expansion of the forces of production – of ‘wealth’, of ‘capital’. This expansion rapidly becomes the extension and the develop ment of the knowledge necessary for increased production, that is to say, of technology and science. Finally, the tendency toward ‘rationally’ re organizing and reconstructing all spheres of social life – production, administration, education, culture, etc. – transforms the whole institution of society and penetrates ever further into all activities.

But you also know that, despite its pretensions, this institution of society is torn by a host of internal contradictions, that its history is shot through with large-scale social conflicts. In our view, these conflicts basically express the fact that contemporary society is divided asymmetrically and antagonis tically between dominators and dominated, and that this division is expressed, notably, in the facts of exploitation and oppression. From this point of view we ought to say that, defacto, the immense majority of people who live in present-day society ought to be opposed to the established form of the institution of society. But it is equally difficult for us to believe that if such were the case, this society could last for long or even could have lasted until today. A very important question therefore arises. How does this society succeed in maintaining itself and holding itself together when it ‘ought’ to arouse the opposition of the great majority of its members? There is a response to this question that we must eliminate once and for all from our minds, the one characteristic of the old mentality of the Left. This is the idea that the system is held together only through the repression and manipulation of people, in an external and superficial sense of the term manipulation.

This idea is totally false and, what is graver still, it is pernicious because it masks the depth of the social and political problem. If we truly want to struggle against the system and, also, if we want to see the problems which, for example, today confront a movement like the ecology movement, we have to comprehend an elementary truth that will seem very disagreeable to certain people : The system holds together because it succeeds in creating people’s adherence to the way things are [ce qui est] . It succeeds in creating, somehow or other, for the majority of people and over the great majority of the moments of their life, their adherence to the effective, instituted, concrete way of life of this society. If we want to engage in an activity that is not vain and futile, it is from a recognition ofthis fundamental fact that we must begin our efforts.

This adherence is, of course, contradictory. It goes hand in hand with moments of revolt against the system. But it nevertheless is a form of adherence, and it is not mere passivity. Just look around you and you can easily see it. Moreover, if people didn’t effectively adhere to the system, everything would collapse in the next six hours. To take just one example: that marvel of ‘organization’ and ‘rationality’ that is the capitalist factory – or, more generally, every capitalist business enterprise, in the West as in the East – would then produce nothing at all, it would quickly collapse under the weight of its absurd regulations and of the internal antinomies characteristic of its pseudorationality if the labouring population did not make it function half the time against the regulations – and quite beyond what could ever be explained by coercion or by the effect of ‘material stimulants’ .

This adherence depends on extremely complex processes, which there can be no question of analysing here. These processes constitute what I call the social fabrication of the individual and of individuals of us all – in and through instituted capitalist society, such as it exists.

I shall simply mention two aspects of this fabrication process. One concerns the instillation in people, from their most tender infancy, of a relationship to authority, of a certain type of relationship to a certain type of authority. And the other, the instillation in people of a set of ‘needs’, to the ‘satisfaction’ of which they will then be harnessed their whole life long.

First, authority. When one looks at contemporary society and one compares it to previous societies, one notes one important difference: today, authority is presented as desacralized; no more are there kings by the grace of God.

DANIEL COHN-BENDIT: You are in Belgium.

CASTORIADIS: I am not forgetting that I am in Belgium. But I do not believe that the king ofthe Belgians is considered a king by the grace ofGod. I think that this must be a principle of Belgian constitutional law, that if there is a king of the Belgians, it is because the Belgian people have sovereignly decided to have a king – no? [Laughter.]

One would think, then, that authority today is desacralized. But in reality it is not. What, in former times, sacralized-authority was religion: as Saint Paul said in Romans, ‘There is no power but ofGod.’ Today, something else has taken the place of religion and of God, something that is not for us ‘sacred’ but which has succeeded, somehow or other, in setting itself up as the prac tical equivalent of the sacred, a sort of substitute for religion, a flat and deflated religion. And this is the idea, the representation, the imaginary signification of knowledge and of technique.

I do not mean thereby, of course, that those who exercise power ‘know’ . But they pretend to know and it is in the name of this alleged knowledge – specialized, s,cientific, technical knowledge – that they justify their power in the eyes of the populace. And if they are able to do so, it is because the popu lation believes this, it is because the populace has been trained to believe this.

Thus, in France one is saddled with a president of the Republic who claims to be an economic specialist. This ‘specialist’, when he was Minister ofFinance, held forth in the Chamber ofDeputies with a three-hour speech in which he laid out statistics rounded to four decimal places. This means he would have flunked first-year economics, since when it comes to prices and production a four-decimal statistic is strictly meaningless: at best, in these areas, one can speak about roughly 10 per cent. That did not stop President Giscard, who is not an economist, from unearthing a dinosaur of conomic knowledge by the name of Raymond Barre[laughter and applause], whom he publicly baptized as ‘the best economist in France’. The result is that the mess the French economy is in at present is much greater than it was three years ago and also than what it would have been had a cleaning lady been prime minister. [Laughter.]

There is a practical conclusion to be drawn from this. There is a field of struggle, especially for people like us here who are more or less involved in intellectual or scientific activities. It is a matter of showing, in the first place, that in the present age power is not knowledge, that not only does it not know everything but even that it knows many fewer things than people in general know, and that there are profound and organic reasons for this. And in the second place, it is a matter of showing that this ‘knowledge’ claimed by power, even when it does exist, is at bottom of a quite particular, partial, and biased character.

But there is also a question I do not want to pass over in silence – although it is only one of the questions we will have to dwell on this evening. It is that – forgetting completely now about Messrs Giscard, Barre, and their fellow plotters – there is a genuine problem of knowledge, and even of technique, that really does challenge us in as much as this knowledge and even this technique go beyond [depassent] the present institution of society. Even if one grants – as I do – that the orientation, the ends, the mode of trans mission, and internal organization of scientific knowledge are anchored in the present-day social system and, even more, that they are, in a sense, consubstantial with it; even then it must be granted that here there is a creation of something that certainly outstrips [depasse] the contemporary era. This is also true, moreover, for previous eras of history. To take one easy example, Pythagoras’s theorem was discovered and demonstrated on Samos or wherever twenty-five centuries ago. Clearly, it was discovered in a context that in no way was ‘neutral’, this context being formed as it was by a set of imaginary schemata indissociably and profoundly tied to the Greek conception of the world, to the Greek imaginary institution of the world, as is the case for all Greek geometry. That does not prevent, twenty-five centuries later, Pythagoras’s theorem, or something that has the same name, not only from continuing to ‘be true’ (one can add as many quotation marks and question marks to this expression as one wishes), but also from appearing infinitely truer than Pythagoras himself could have thought it to be, since the present statement ofPythagoras’s theorem, such as you will find it in a contemporary analytical geometry textbook, con stitutes an immense generalization ofits original formulation. It is still called Pythagoras’s theorem, but now it states: In every pre-Hilbertian space, the square of the measure of the sum of two orthogonal vectors is equal to the sum of the squares of their measures. Or, to take another example, no society is possible without arithmetic – no matter how archaic, primitive, or savage this society might be. But where, then, does arithmetic stop? This, too, is part of the question of knowledge. It is too easy to evacuate this ques tion by saying, as a recent small-minded Parisian clown [microfarceur] said, that totalitarianism is the scientists in power, which evidently serves only to condone and to reinforce the dominant ideological mystification. As if Stalin, who directed the operations of the Russian Army during the Second World War on an ordinary globe, as Khrushchev revealed, was a ‘scientist in power’! But it is also too easy to evacuate the question, as is often done in our circles and by people close to us, by trying to jettison science and tech nique as such because they are said to be the pure products of the established system; one would thus end up eliminating any interrogations bearing on the world, on ourselves, on our knowledge.

I come now to the other dimension of the process whereby the individual is socially fabricated, that concerning ‘needs’. Quite evidently, the human being has no ‘natural needs’, in any definition of the term natural – save, perhaps, in a philosophical definition in which ‘nature’ would be something completely different from what you usually think of under this term: a ‘nature’ according to Aristotle, or Spinoza, something like a norm that is both ideal and real. Beyond the fact that we are not here tonight to discuss these kinds of philosophical questions, this acceptation ‘of the term nature does not interest us for a precise reason: it is unclear how one could agree socially on how to defme what would cor:respond to a ‘nature’ of that kind.

There are no natural needs. Every society creates a set of needs for its members and teaches them that life is not worth living, and cannot even be lived physically, unless those created needs are ‘satisfied’ somehow or other. What is capitalism’s specificity in this regard? In the first place, capitalism was able to arise, maintain itself, develop, and become stabilized (despite and along with the intense working-class struggles tearing through its history) only by putting ‘economic’ needs at the centre of everything. A Muslim, or a Hindu, will put aside some money his whole life long in order to make a pilgrimage to Mecca or to some temple; for him, that is a ‘need’ . I t is not one for a n individual fabricated b y capitalist culture: this pilgrimage is a superstition or a whim. But for this same individual it is not a supersti tion or a whim, but an absolute ‘need’, to have a car or to change one’s car every three years, or to have a colour television set as soon as one exists.

In the second place, therefore, capitalism succeeds in creating a humanity for which, more or less and somehow or other, these ‘needs’ are almost all that count in life. In the third place – and this is one of the points radically separating us from a view such as the one Marx could have of capitalist society – these needs that capitalism creates, somehow-or-other-and-most of-the-time it satisfies them. As one says in English, ‘It promises the goods and it delivers the goods’. The junk is there, the stores are overflowing with the stuff- and you have only to work in order to be able to buy some. You have only to be well-behaved and work, and you will earn more, you will clamber up, you will buy more, and there you are. And historical experience shows that, with a few exceptions, it works: production goes on, people work, things are bought, consumption continues, and it works all over again.

At this stage in the discussion, the question is not whether we are ‘criti cizing’ this set of needs from a personal point of view, tastewise, from the human, philosophical, biological, medical, or what have you point of view. The question bears upon the facts, about which one should not nourish any illusions. Briefly speaking, this society works because people yearn to have a car and because they can, in general, have one, and because they can buy petrol for this car. This is why one of the things that might knock down the social system in the West is not ‘pauperization’, whether absolute or rela tive, but, rather, for example, the fact that governments might not be able to furnish drivers with petrol.

We really must realize what this means. When we speak of the energy problem, nuclear power, and so on, what in fact is involved is the entire political and social functioning of society, and the whole contemporary way oflife. It is so both ‘objectively’ and from people’s point of view, and in this regard our criticisms of the brutality of a consumer society count for little.

This situation may easily be illustrated by means of the future – and already past and present – political speeches of citizen [and Communist Party leader Georges] Marchais, who explains ( 1 ) if you no longer have any petrol to drive around with, it is the fault of the trusts, the multinationals, and of the government that is in bed with them; and (2) if the Communist Party comes to power, it will give you petrol because it will not be subject to the multinationals and because our great ally, friend of the French people, and great oil producer the Soviet Union will provide us with petrol (little matter if things are starting to go very badly over there, too, in this regard as well). That, clearly, is one possible scenario, just as there exists a possible scenario from an apparently opposite quarter, that is to say, from a neo-Fascist demagogue who might emerge from an energy crisis and the attendant fallout.

The energy crisis has meaning as a crisis, and is a crisis, only in relation to the present model of society. It is this society that has need, each year, of 1 0 per cent more oil or energy in order to be able to keep running. This means that the energy crisis is, in a sense, a crisis of this society. Thus, it contains in germ – and here is a question to which it is for you, much more than for me, to respond – a challenge on people’s part to the whole system. But perhaps it contains, as well, in germinal form the possibility that people will follow the most aberrant, the most monstrous political currents. For, this society, such as it is, probably could not continue if the process of ever increased consumption did not keep droning on. It might be able to chal lenge itselfby saying: What we are doing is completely mad, the way we live is absurd. But it could also cling to the present-day way of life, saying to itself: This or that party has the solution; or, We only have to kick out the Jews, the Arabs, or whoever, in order to solve our problems.

This is the question that is posed, and I pose it now to you: Where are people now at, concerning the crisis of their way of life? And what might a lucid political activity be that would accelerate the raising of people’s consciousness concerning the absurdity ofthe system and would aid them in sorting things out among the various critiques of the system already now forming both on the Right and on the Left.

I now would like to broach, in immediate connection with the foregoing, the question of the ecology movement. It seems to me that one can observe, in the history of modern society, a sort of evolution in the field on which challenges, contestation, revolts, and revolutions take place. It also seems to me that one can shed some light on this evolution if one looks at the two dimensions of the institution of society I mentioned earlier: the instillation in individuals of a scheme of authority and the instillation in individuals of a scheme of needs. From the outset, the workers’ movement challenged the entire organization of society, but it did so in a way that, retrospectively, cannot help but appear to us to be somewhat abstract. What the workers’ movement attacked above all was the dimension of authority – that is to say, domination, which is its ‘objective’ side_. Even on this point it left in the shadows – as was almost inevitable at the time – some completely decisive aspects of the problem of authority and domination, therefore also political problems concerning the reconstruction of an autonomous society. Some of these aspects were put into question later on, and especially, more recently, by the women’s movement and the youth movement, both ofwhich attacked the schemata, the figures, and the relations of authority as these existed in other spheres of social life.

What the ecology movement has put into question, on its side, is the other dimension: the scheme and structure of needs, the way of life, of society. And this constitutes a capital breakthrough [depassement] in comparison with what can be seen as the unilateral character of previous movements. What is at issue in the ecology movement is the entire conception, the entire position of the relations between humanity and the world, and ultimately the central and eternal question: What is human life? What are we living for?

To this question there already exists, as we know, an answer: it is the capitalist response. Allow me here to open a parenthesis, proceeding rapidly in reverse. The most beautiful and concise formulation of the spirit of capitalism I know ofis Descartes’s well-known programmatic statement: We are to attain knowledge and truth in order to ‘make ourselves masters and possessors of nature’. It is in this statement of the great rationalist philoso pher that one sees most clearly the illusion, the madness, the absurdity of capitalism (as well as of a certain philosophy and a certain theology that precedes it). What does it mean to ‘make ourselves the masters and posses sors of nature’? Note, too, that both capitalism and the work of Marx and ofMarxism are founded upon this meaningless idea.

Now, what becomes apparent, perhaps in fits and starts, through the ecology movement is that we certainly do not want to be masters and posses sors of nature. First of all, because we have understood that this does not mean anything, it has no meaning – except to enslave society to an absurd project and to the structures of domination embodying that project. And next, because we want another relationship with nature and with the world – which means, too, another way of life and other needs .

The question, however, is this: What way of life, and what needs? What do we want? And who can answer to these questions, how, and on what basis? By answer I mean not in a state of absolute knowledge but, rather, in full knowledge of the relevant facts and lucidly.

In my view, the ecology movement has appeared as one ofthe movements that tend toward the autonomy of society. Each time I have spoken of it, either orally or in writing, I have included it in the series of those movements I just mentioned. In the ecology movement it is a matter, in the first place, of autonomy in relation to a technico-productive system that is alleged to be inevitable or optimal, the technico-productive system present in society today. But it is absolutely certain that, by the questions it raises, the ecology movement goes far beyond this question of the technico-productive system, since it engages potentially the entire political problem and the entire social problem. I shall explain myself here and end on this point.

That the ecology movement engages the entire political problem and the entire social problem can immediately be seen by starting with an apparently limited question. I hope you will excuse me if I tell you things you must already have heard dozens of times, and if I say them abruptly. The anti nuclear struggle: Yes, very good, bravo. But does that mean at the same time an antielectricity struggle? If yes, then one must say so, right away, loud and clear. And one must also say: We are against electricity and we know all the implications ofwhat we are saying: no sound system in a hall like this one – but that’s already happened [laughter]; no telephones; no surgery rooms (after all, Illich says medicine only increases the mortality rate); no radio, pirated or otherwise; no tape recorders; no Keith.Jarrett records like the one I just heard in your club, and so on. It must be realized that there is practi cally no object of modern-day life that in one way or another, directly or indirectly, does not imply electricity. This total rejection is perhaps accept able – but one must know it and say it.

Or else, the only logical thing would be to propose other sources of energy, stating and showing that it is not necessary to deprive oneself of electricity if one rules out nuclear power plants, provided that the entire system of energy production be reformed in such a way that only renewable sources of energy would be allowed. As I am sure you know many more things than I do about renewable energy sources, I won’t bother to extend my remarks on this question considered in its own right. But the question of renewable energy sources goes far beyond the question of renewable energy sources. First, it implies the totality ofproduction. And then (or, rather, at the same time), it implies the totality of social organization. The only attempt I personally know of to take the question in its entirety into account is the Alter project Philippe Courrege is working on in France with a tiny group of volunteer workers. I say seriously because Courrege saw straight away that it is not only a question of ensuring the production of renewable sources of energy; he saw that this implies the totality ofproduction and, consequently, he proceeded to construct a small complete ‘system’ (or, rather, a broad range of such systems, each depending upon the final objectives one sets for oneself), a closed matrix covering the totality of ‘inputs’ and ‘ outputs’ of a small, fairly much autarkic region. But I also say seriously because Courrege

also saw, and said, that what on the ‘technical’ or ‘economic’ level is, if not a simple solution, at least a feasible one raises immense political and social (he says ‘societal’) problems: the definition ofthe final objective ofproduc tion, the community’s acceptance of a steady state, the management of the whole, and so on. Here I can say I feel I am on familiar ground – not that I, of course, have the solution, but because these are the questions on which I have been reflecting and working for thirtY years and they become both more precise and more clear when one gives concrete underpinning to the idea of self-governed social units living in large part upon locally renewable resources. But there remains the ‘negative’ aspect, so to speak, which the Alter project also shows: if one wants to touch upon the problem of energy, one has to touch upon everything. Now, all that is neither theory nor literary posturing. As is known, governments are saying even now that without nuclear power plants there will be no more electricity in a few years. Certainly, if nothing else happens – and as, since 1 973, these governments have done nothing but blow hot air on the energy problem without doing anything real about it – we really will end with something happening like the breakdown of the power grid last year in France.

Now, on the other hand, projects that deal with renewable energy resources can,in part be co-opted towards ends that could not even be labelled reformist – that is, toward the end of plugging up the holes in the existing system. And beyond this question of co-option, this leads to another question: Does an antinuclear, energy-oriented ecological ‘reformism’ have any meaning and can it be lucidly supported? I mean here by ‘reformism’ the support given to partial measures we consider viable and meaningful (that is to say, those not cancelled out by the very fact that they are inserted into an overall system that, itself, is not changed); for example, the laws against the pollution of waterways – laws that leave everything else in place: multinational companies, the State, the Communist Party, the king, etc. A certain traditional position responded in the negative to this question. It was said: We are fighting for the Revolution, and one of the by products of the Revolution will be the nonpollution of rivers (as well as the emancipation of women, the reform of education, etc.) . We know that this response is absurd and mystificatory, and fortunately women and students have stopped waiting for the Revolution to demand and obtain real changes in their condition. I think that the same thing holds for the ecology strug gle: there is, for example and among a thousand other issues, a grave question of the pollution of waterways, and the struggle against this state of affairs makes complete sense, provided one·knows what one is doing, pro vided one is lucid. This means that one knows that at present one is struggling for this or that partial objective because it has a certain value, and that one knows, too, that the measure of which one is demanding the intro duction or the implementation will, so long as the present system exists, necessarily have an ambiguous signification and can even be diverted from its initial objective. You know that Social Security was, in many countries,

a conquest wrested by the working class in the midst of struggle. But you know, too, that there are Marxists who explain – and after all, it is not totally false from a certain point ofview – that Social Security makes the capitalist system function because it serves the upkeep of the labour force. Well, so what? Should one demand the abolition of Social Security on the basis of that argument?

I shall close in broaching the problem that to me seems the most profound, the most critical – critical in the initial sense of the word crisis: the moment and process of decision. To speak of an autonomous society, of the autonomy of society, not only with regard to this or that particular dominant stratum but with regard to its own institution, needs, techniques, etc., pre supposes both the capacity and the will of human beings to govern themselves in the strongest sense of this term. For a very long time, in fact from the beginning of the period I was engaged in Socialisme ou Barbarie with my comrades, it was basically in these terms that for me the question of the possibility of a radical, revolutionary trans formation of society was formulated: Do human beings have the capacity and especially the will to govern themselves? (I say especially wz11 to gov ern themselves, for in my view ‘capacity’ does not really pose a problem.) Do they truly want to be their own masters? For, after all, if they really wanted it, nothing could stop them: this has been known since Rosa Luxemburg, since La BOt!tie, even since the Greeks. But little by little another aspect of this question – the question of the possibility of a radical transformation of society – began to appear to me, and to preoccupy me more and more. It is that another society, an autonomous society, does not imply only self-management, self-government, self-institution. It implies another culture, in the most profound sense of this term. It implies another way of life, other needs, other orientations for human life. You will agree with me if I say that a socialism of traffic jams is an absurd contradiction in terms and that the socialist solution to this problem would not be to eliminate traffic jams by quadrupling the width of the Champs Elysees. What are these cities, then? What do the people who fill them truly desire to do? How the devil does it happen that they ‘prefer’ to have their cars and spend hours each day in traffic jams, rather than something else?

To pose the problem of a new society is to pose the problem of an extra ordinary cultural creation. And the question that is posed, and that I pose to you, is the following: Do we have, before us, some precursory and pre monitory signs of this cultural creation? We who reject, at least in words, the capitalist way of life and what it involves – and it involves every thing, absolutely everything that exists today – do we see coming to life around us another way of life that heralds, that prefigures something new, something that would give some substantive content to the idea of self management, self-government, autonomy, self-institution? In other words, can the idea of self-government take on its full force, attain its full appeal, if it is not also borne by other desires, by other ‘needs’ that cannot be satisfied within the contemporary social system?

The rest of us, probably, we who are here, can no doubt think of such needs, we feel them, and perhaps for us they count for a lot. For example, I don’t know, to be able to go when one wants to wander in the woods for two days. But the question does not lie there. At issue are not our wishes and needs, but those of the great mass of people. What is being asked is this: Is something of this sort, a rejection of the needs being nourished at present by the system and the appearance of other aims, beginning to dawn, to appear to be important to people living today?

And finally, what is being asked is this: Don’t we effectively encounter on this point, on this line, the limit to political thought and action? Like all thought and all action, this kind, too, must have a limit – and must endeav our to recognize it. Is not this limit, on this point, the following: that neither we ourselves nor anyone else can decide on a way of life for others? We are saying, we can say, we have the right to say that we are against the contemporary way of life – which, once again, implies nearly everything that exists and not only the construction of such and such a nuclear power plant, which is only one ofits implications to the nth degree. But to say that we are against such a way of life introduces, in a roundabout way, a tremendous problem, what can be called the problem of right in the most general sense, not simply formal rights, but right in terms of content. What is going to happen if others continue to want this other way of life? I inten tionally take an extreme and absurd example, since it is close to the starting point of our meeting. Suppose there were people who not only want electricity but specifically want electricity of nuclear origin? You offer them all the electricity in the world, but they don’t want it: they want it to be nuclear. All sorts of tastes exist in nature, after all. What would you say in such a case, what shall we say? We will say, I suppose, that there will be a majority decision (at least we hope it will be) that forbids people from sat isfying their taste for nuclear-powered electricity. Again, this is an absurd example – and one easy to resolve. But you can easily imagine thousands of others that are neither absurd nor easy to resolve, for what is posed in this issue of one’s way of life is ultimately the following question: How far can the ‘right’ (the legally and collectively assured effective possibility) of each individual, of each group, of each commune, of each nation to act as it wants, extend once we know – and we have always known it, but the ecology movement forcefully reminds us of it – that we are all embarked on the same planetary boat and that what each one of us does can have repercussions on everyone else? The question of self-government, of the autonomy of society, is also the question of the self-limitation of society. Self-limitation has two sides to it: limitation by the society of what it con siders to be the unacceptable wishes, tendencies, acts, and so on of this or that portion of its members, but also self-limitation of society itself in its rules and regulations, the legislative authority it exercises over its members. The positive and substantive problem ofright lies in the ability to conceive a society that is founded upon substantive universal rules (the prohibition of murder is not a ‘formal’ rule) and at the same time is compatible with

the greatest possible diversity of cultural creation and therefore also of ways of life and systems of needs (I am · not talking here about folklore for tourists) . And this synthesis, this conciliation is not something we can just pull out of our heads . It will come out of society itself, or it will not come out at all.

To recognize this limit to political thought and to political action is to prohibit oneself from redoing the work of the political philosophers of the past, substituting oneself for society and deciding, as Plato and even Aristotle did, that some musical scale is good for the education of the young, whereas some other one is bad and ought therefore to be banned from the city. This in no way implies that we are to renounce our own thinking, our own action, our own point of view, or that we are to accept blindly and religiously all that society and history can produce. Again, it is ultimately an abstract philosophical point of view that led Marx to decide (for it was he who decided) that what history will decide or has already decided is good. (History almost decided for the Gulag.) We maintain our responsibility, our judgement, our thought, and our action, but we also recognize the limit thereto. And to recognize this limit is to give full con tent to what at bottom·we are saying, namely, that first and foremost a revolutionary politics today entails recognition of people’s autonomy, that is to say, the recognition of society itself as the ultimate source of institu tional creation. [Applause.]