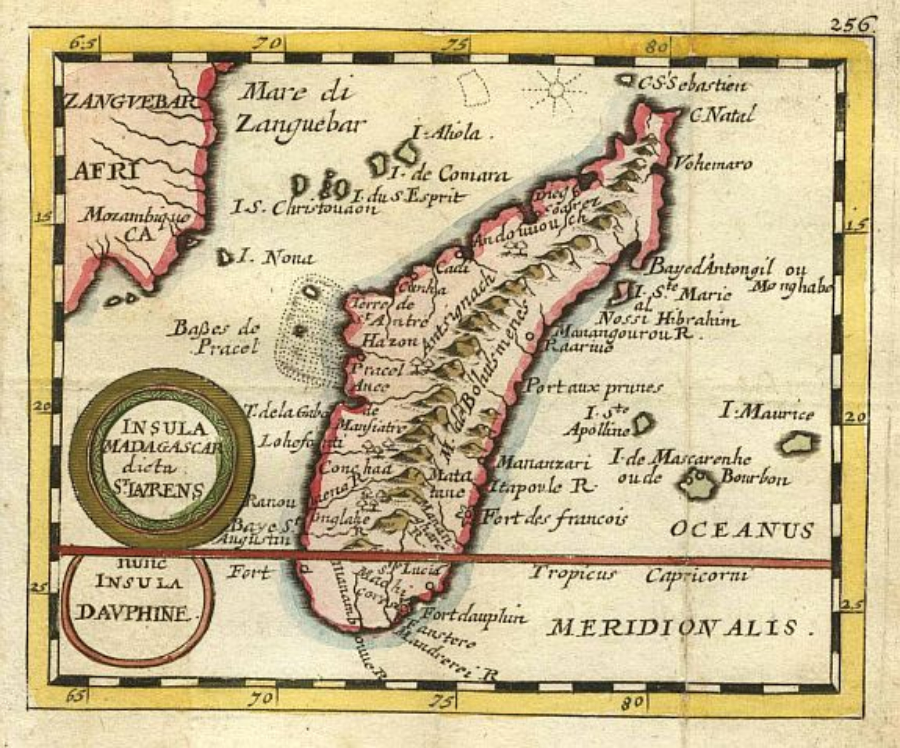

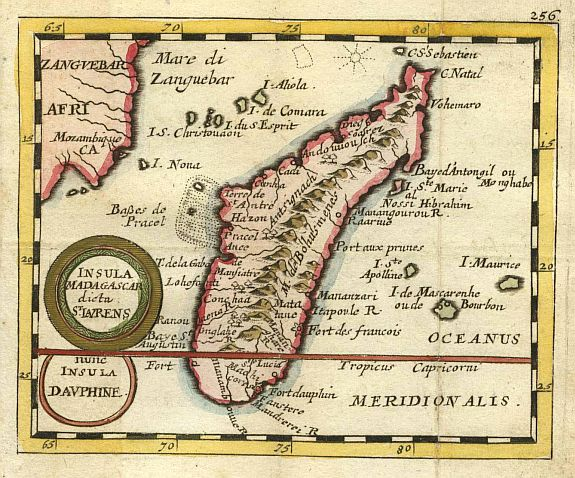

Libertalia was a pirate utopia created in the later 17th century in Madagascar under the leadership of Captain James Mission. Although there is no evidence that Libertalia really existed, it certainly exists in the vast imaginary repertoire of possible future utopian experiments. According to the legends and written evidence, the pirates abolished slavery, practiced direct democracy, created a new language, and operated a social economy.

The anthropologist David Graeber, whose first field trips were to Madagascar to research pirates, writes in his posthumously published book The Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia:

(…) stories about Libertalia, or for that matter Avery’s pirate kingdom, were in no sense isolated fantasies. What’s more, their very existence and popularity was a historical phenomenon in its own right. In a certain sense these stories might even be said, to adopt Marx’s phrase, to be a material force in history. After all, the Golden Age of Piracy, as it’s now called, really lasted only forty or fifty years; it was quite some time ago; but people all over the world are still telling stories about pirates and pirate utopias—or for that matter, elaborating on them with the kinds of kaleidoscopic fantasies about magic, sex, and death that, as we’ll see, have always accompanied them. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that these stories endure because they embody a certain vision of human freedom, one that still feels relevant—but one, at the same time, that offers an alternative to the visions of freedom that were to be adopted in European salons over the course of the eighteenth century, and that still remain dominant today. The toothless or peg-legged buccaneer hoisting a flag of defiance against the world, drinking and feasting to a stupor on stolen loot, fleeing at the first sign of serious opposition, leaving only tall tales and confusion in his wake, is, perhaps, just as much a figure of the Enlightenment as Voltaire or Adam Smith, but he also represents a profoundly proletarian vision of liberation, necessarily violent and ephemeral. Modern factory discipline was born on ships and on plantations. It was only later that budding industrialists adopted those techniques of turning humans into machines into cities like Manchester and Birmingham. One might call pirate legends, then, the most important form of poetic expression produced by that emerging North Atlantic proletariat whose exploitation laid the ground for the industrial revolution. As long as those forms of discipline, or their more subtle and insidious modern incarnations, govern our working lives, we will always fantasize about buccaneers.

Read the excerpt from David Graeber’s preface to Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia here